By James F. Caccamo

Ex Libris, Vol V, Number IV (April 1983)

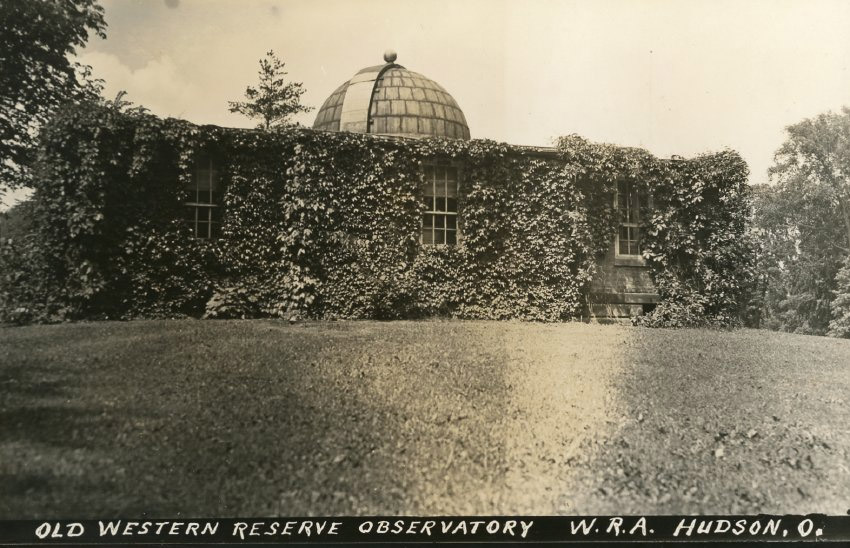

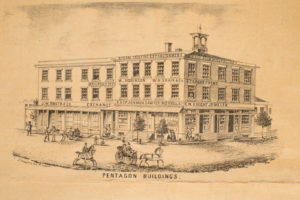

Western Reserve College owned a prime piece of land in the 1840’s, and Henry Noble Day, the Professor of Sacred Rhetoric at the College had an idea. In 1849, those facts merged, and the end result was the Pentagon Building, one of the largest structures ever erected in 19th Century Hudson.

The property was an irregularly-shaped piece of land at the northwest corner of College and Aurora Streets. Day, always the entrepreneur, convinced the college trustees to permit him to develop the land for commercial purposes. Day also managed to receive a loan from the College to commence construction, and an option to buy the College’s title to the building at a later date. Day was banking on another big railroad boom in Hudson, similar to that which occurred a short time earlier when the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad came through town. A new venture, the Clinton Line Railroad, looked even more promising, and Day knew that a new railroad would mean an increased need for commercial space in Hudson.

At first, Day was right. He had no trouble finding tenants for the building, and certainly had no trouble meeting his monthly rent to the college of $176 per year and the interest that he owned them on a $3,000 loan for the construction.

Among Day’s tenants were the Sawyer-Ingersoll Book Publishing Co., a firm that saw enormous success in the 1850’s; the offices of the Ohio Observer, the local newspaper; a dry goods store called J.W. Smith & Co., in which Day was a silent partner; the Western Reserve Drug Store, in which Day was also a partner; a day school; a furniture store; the jewelry store of C.M. Knight; and the offices of the Clinton Line Railroad, among others.

Unfortunately, Hudson’s business boom collapsed with the Clinton Line Railroad, and with it went much of the profitability of the Pentagon Building. Instead of a shortage of office space, Hudson now had a surplus. Day was never able to gain control of the Pentagon, and it remained in college hands for a number of years.

In 1878, Seymour Straight built his cheese warehouse to the north of the Pentagon, and bought the Pentagon for his business (the warehouse today is Western Reserve Academy’s Hayden Hall). Straight paid $7,000 for the building.

Straight & Son continued to use the building, but soon it became a derelict and an eyesore. By the turn of the century, it was obvious that the Pentagon was rapidly becoming a symbol of Hudson’s decline.

In 1909, with some prompting from James W. Ellsworth, the building was torn down. Part of the land was used as the site for the new parsonage for the Congregational Church. Soon after the Pentagon Building’s demise, Ellsworth remodeled the 1878 cheese warehouse built by Straight, and converted it into the Hudson Club House.

Why mourn the loss of the Pentagon Building? After all, it was a huge, ungainly, three-story building. At the time of its demolition, it was a dreary mass of broken windows and peeling paint. The answer lies partly in the fact that the Pentagon Building was one of the structures that was constructed by Frederick W. Bunnell, the builder whose work can be seen today in the Brewster Mansion and the Congregational Church. The Pentagon would have given modern architectural historians some new perspectives of Bunnell’s work.

Another factor to be considered is that the Pentagon was in fact a precursor to the shopping mall. It was a conglomerate of shops and businesses removed from the center of town.

Finally, the very size of the Pentagon alone makes it fascinating in terms of Hudson’s architectural history.

The Pentagon Building, like the other buildings of “lost Hudson” is a fading memory. As with Evamere and Christ Church Episcopal, its loss permanently altered the look of Hudson.